At a Glance

- After the $35/oz peg broke in 1971, gold surged and peaked at $850 on the London market in 1980.

- Backdrop: the collapse of Bretton Woods (Nixon Shock, 1971-08-15), the oil shocks (1973, 1979), stagflation (double-digit inflation), and geopolitical risks (Iranian Revolution, Soviet invasion of Afghanistan).

- When monetary-system change, deeply negative real rates, and geopolitical stress overlap, gold acts as an inflation hedge and store of confidence. The cycle ended as Volcker’s tightening (1979-10) broke inflation.

How Much Did Gold Rise in the 1970s?

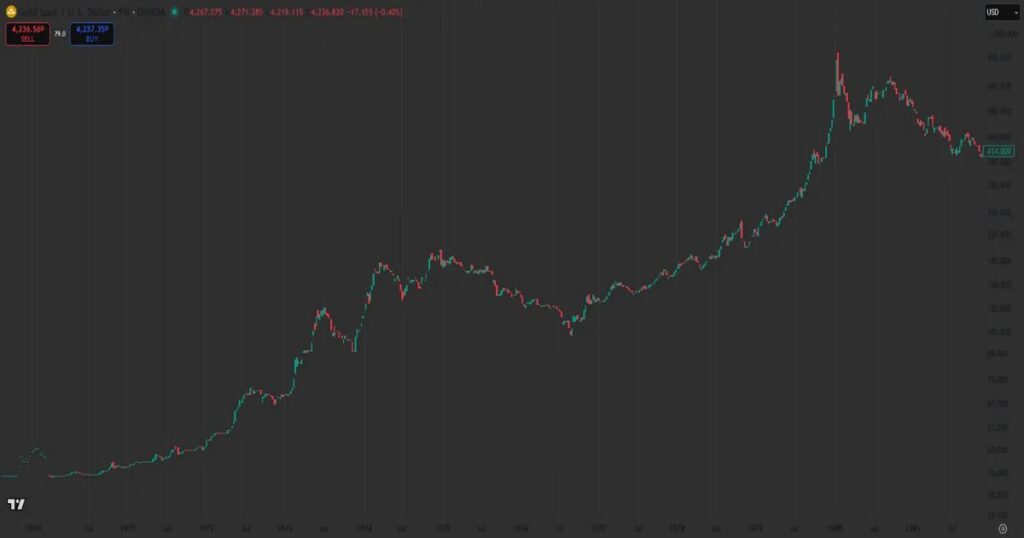

From 1968–1971, the dollar–gold convertibility effectively held gold near $35/oz. After the Nixon Shock (1971) ended convertibility, the gold standard effectively ended.

With the move to floating exchange rates, gold spiked in 1974, corrected in 1976, and then surged again in 1979–1980. The final top came on 1980-01-21, when the London fixing hit $850, capping a nine-year secular bull market.

Historical Background of the 1970s

- 1971-08 — Nixon Shock: To tackle inflation and trade problems, the U.S. suspended dollar–gold convertibility, effectively ending the Bretton Woods gold-exchange standard centered on the dollar.

- 1973–1974 — First Oil Shock: OAPEC’s embargo sent oil prices up roughly fourfold, triggering global inflation and recession (stagflation).

- 1979–1980 — Second Oil Shock: The Iranian Revolution disrupted supply, and fears surrounding the Iran–Iraq War drove oil higher again.

- 1979-10 — Volcker’s Anti-Inflation Turn: The Fed shifted to strict monetary targeting and aggressive tightening; as inflation expectations fell, the gold cycle effectively ended.

Why Did Gold Climb So Relentlessly?

Break with the monetary regime (end of convertibility).

Without dollar–gold convertibility, investors sought inflation hedges and monetary “trust,” channeling demand into gold. Floating rates also freed price discovery.

Stagflation and high inflation.

By the late 1970s, double-digit CPI made gold the go-to purchasing-power preservative.

Oil shocks → cost push → inflation expectations.

The 1973 and 1979 oil shocks lifted costs and inflation, pushing real rates (nominal – inflation) negative, a favorable environment for gold.

Rising geopolitical risk.

The Iranian Revolution (1979) and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979) boosted safe-haven demand.

What We Should Learn Today

The combination of macro drivers matters.

When monetary-system change, inflation/real rates, oil, and geopolitics move together, gold’s demand regime can shift. The 1970s is a textbook case of an extreme bullish combination.

Real rates are the key switch.

More than nominal yields, real yields determine gold’s friend/foe regime. After Volcker’s tightening (1979-10) normalized real rates, the gold bubble faded. (In recent years, some argue the correlation between gold and real rates has weakened—see our separate note: Gold vs. Real Rates.)

Tops form at the peak of the narrative.

The January 1980 top coincided with the maximum of inflation fear, geopolitical shocks, and policy uncertainty. Connecting data + geopolitics + policy helps explain peaks.

References

Nixon Shock & end of Bretton Woods: Federal Reserve History; Wikipedia

Oil shocks: U.S. Office of the Historian; Fed History (1979 oil shock)

Volcker’s 1979 shift: Federal Reserve History; FRB/FEDS papers

![[URGENT] Gold-Silver Ratio Breaks Below 60!](https://goldkimp.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/gold-silver-ratio-hits-60-historic-low-image.jpg)